Kalighat Painting

@Asim Deb

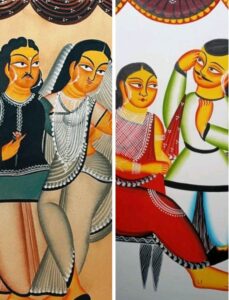

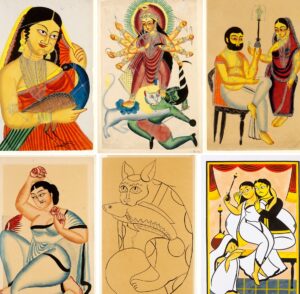

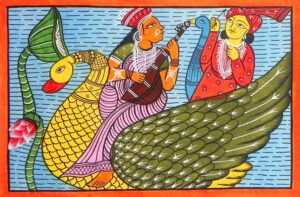

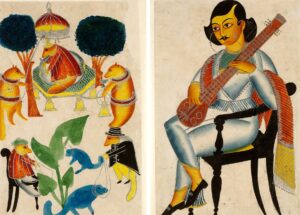

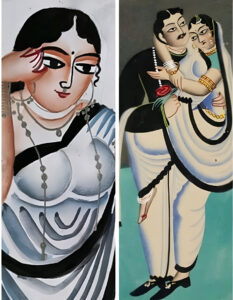

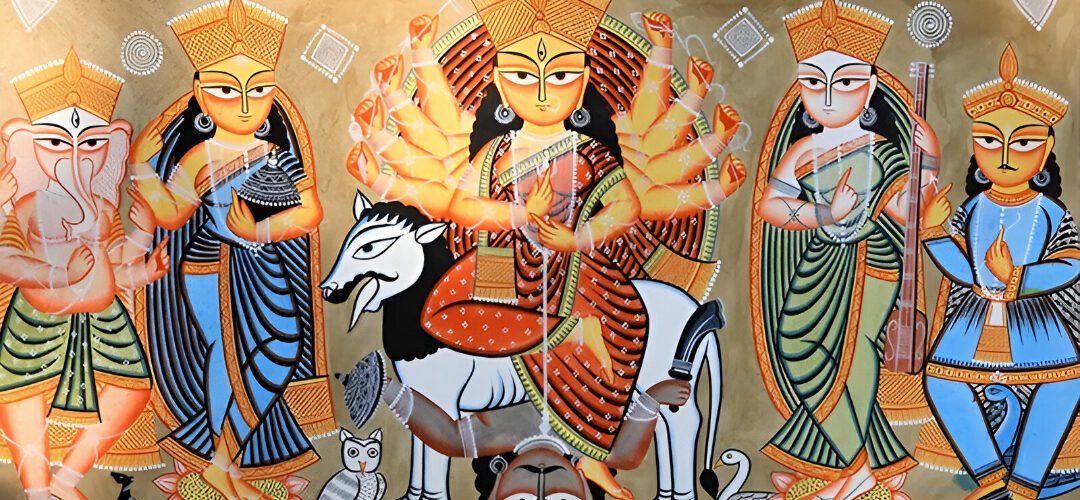

Kalighat Painting evolved in the 19th century at Kalighat area of Kolkata. Characterised by its bright colours and bold outlines with sweeping brush strokes and strong lines, it became a unique class of Indian painting. Initially from the depiction of Gods and other mythological character, these paintings were originally intended to be souvenirs for devotees visiting the Kali temple and featured mainly Hindu Gods & Goddess, later the art expanded over time to include other religious traditions as well as socio-political commentary.

“The drawing is made with one long bold sweep of the brush in which not the faintest suspicion of even a momentary indecision, not the slightest tremor, can be detected. Often the line takes in the whole figure in such a way that it defies you to say where the artist’s brush first touched the paper or where it finished its work…”

As the Kalighat paintings were undated, unsigned and drawn by so many individuals, the names of most artists remain unknown. The last well-known Kalighat artists, Nibaran Chandra Ghosh and Kali Charan Ghosh, passed away in 1930, but Kalighat paintings influenced subsequent generations of Indian artists, most notably Jamini Roy, and more recently the Midnapore-based contemporary artist Uttam Chitrakar. However, the artists, known as ‘Patuas’ had to produce and sale their works of art at a very cheap rate to make a living.

Origins of Kalighat Painting

From the late 17th century, when the place was a part of the city of Kolkata, it was already known as the sacred realm of Hindu Goddess Kali. By early 19th century, the temple was a popular destination for local people, pilgrims and many European visitors. Slowly Kolkata developed into a busy and thriving industrial harbour city, migrants began arriving looking for new opportunities. Artisans, craftsmen and painters from various places of India, including Patuas, an artisan community of West Bengal.

The Patuas traditionally described long narrative stories in the form of painting, and often these were over 20 feet in length. However, being influenced by the different other art forms and to present a work in quick time, the Patuas abandoned their traditional narrative style in favour of single pictures with minimum figures, and using most basic combinations of colours. They could get imported cheaper readymade paints and papers from Britain. So, the paintings were easily made on mill-paper treated with a paste of lime, on which watercolours were dabbed using a large brush or a rag. The pigments used were derived from available sources like black from lampblack, red from lead, yellow from arsenic and blue from indigo. Black outline was drawn using a pencil or a brush made from squirrel or goat hair, after which paint was reapplied to the edges that needed shading.

Some of the colours were also made of indigenous ingredients, for example yellow from turmeric root, blue was made from petals of Aparajita flower, and black was produced from common shoot by burning an oil lamp under a pot. Silvery and golden colours were also used for ornamentation. Artists used colloidal tin extensively as a substitute of silver to embellish their paintings and replicate the surface effects of jewels and pearls. Along with the colours, gum of Bel fruit or crushed tamarind seeds was used as binder.

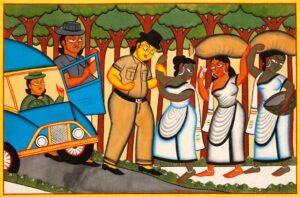

In the beginning Kalighat paintings portrayed Hindu Gods and Goddess mostly worshipped by the Bengali community, and also the life of Krishna, Ramayana and Mahabharata. As the Kalighat style gained popularity, groups other than the Patuas took up the profession. Mid 19th century onwards, the paintings began with themes of contemporary, and satirical subjects, socio-cultural and political themes, ranging from freedom fighters Rani Lakshmibai of Jhansi, and Tipu Sultan, to themes as courtesan culture, domestic pets, horse racing, wrestling, among others. The rise of ‘Babu culture’ in late eighteenth century was well envisaged sarcastically by the Patuas. Also the upper class Indian husbands cowering before their wives, possibly as opportune references to Durga or Kali.

In 1873, following an affair between Nabinchandra Banerji’s young wife Elokeshi with the Chief Priest of the Shiva temple at Tarakeshwar. Nabinchandra Banerji cut Elokeshi’s throat with a fish knife (bonti). The incident became famous as Tarakeshwar murder case. Then various paintings on Tarakeswar affair were portrayed in Kalighat repertoire: the meeting of Elokeshi and the mahant at Trakeswar Shiva temple; Elokeshi offering betel and hookah to the Priest, and the Priest is offering her childbirth medicine; Elokeshi embracing Nabin and asking his forgiveness; Murder of Elokeshi by Nabin, courtroom trial of Nabin, ……. all these were portrayed by different Patuas.

*******

Kalighat paintings attracted many foreign travellers who visited the city in the 19th century. As examples of ‘oriental’ or ‘exotic’ souvenirs, Kalighat paintings were easily portable and concise enough to explain to friends back home.

Some scholars believe that the tradition can be traced to the 1830s or earlier when Patua artisans first moved to the city and began making paintings around the temple, while others argue that the thematic and visual characteristics that are more definitive of Kalighat painting, such as political caricatures, hairstyles and ornaments, only go as far as the 1850s. It is, however, broadly accepted that Kalighat painting reached its peak around the mid 1870s and began to decline after the late 1880s, owing to the rising popularity of photography and printing technology imported from England and Germany.

History of Kalighat Paintings: A glimpse

It is believed that the paintings have attained its pinnacle in between 1880 and 1890. A number of skilled artists moved to Kolkata from rural Bengal especially from 24 Paraganas and Midnapore and set up stalls outside the Temple. They painted long narrative stories on scrolls of handmade paper often stretched to over 20 feet in length and were known as POTOCHITRA. The POTUA artist would often travel from village to village, unrolling the scroll to show to the buyers and often would sing the stories to their audiences.

W G Archer finally concluded that the final phase of Kalighat paintings ceased to exist after about 1930. Suhashini Sinha has chronologically categorised the Kalighat painting collections into three broad phases.

1. Phase I: Dated between 1800 and 1850, which attributes the origins of the genre, and the formation of essential Kalighat Characteristics

2. Phase II: Dated between 1850 and 1890, this set depicts many variations between style, composition and colour and has attained its peak in its class

3. Phase III: Dates from 1900 to 1930, which shows the end of the tradition with the infiltration of cheap lithographs.

Characteristics of Kalighat Painting

The key characteristics styles of Kalighat painting are the rounded, tapering limbs and pointed faces with small mouths and elongated, almond-shaped eyes. The neck and limbs may be bent at sharp angles or drawn as fluid curves, allowing the figures to have dynamic poses. Only the human figures are drawn with heavy shading and outlines, giving them a three-dimensionality that was not applied to the backdrop.

Costly and difficult to carry, the interested byuers visiting the city were opting for smaller artworks, and thus, compelling the artisans to create smaller, less detailed but more portable images, which would come to be known as the Kalighat pats. The number of such visitors increased as trains began to connect more parts of the country. Partly because of the patronage of common ordinary people, and partly because the Patua community was already known for their craft, Kalighat paintings could develope a reputation for keeping up with the visual culture of the time.

Kalighat painting today

Kalighat painting began to die out during the early 20th century following the increase in demand for cheaper, commercially produced images. Many Patua families found themselves themselves facing no option but to leave the city and head back to the rural districts where their ancestors had come from, or to look for other forms of employment.

Victoria & Albert Museum (V&A), London

Picture: The policeman’s bribe, Anwar Chitrakar, 2010. Museum no. IS. 49-2011. © Victoria and Albert Museum, London

Picture: The policeman’s bribe, Anwar Chitrakar, 2010. Museum no. IS. 49-2011. © Victoria and Albert Museum, London

Today, the V&A holds the largest collection of Kalighat paintings in the world. The collection, which numbers about 645 watercolour drawings and paintings, also includes line drawings and hand-coloured lithographs. The majority of works are similar to standard A3 paper size though the collection also contains 295 smaller, postcard-sized paintings (roughly 13 cm x 8 cm). Created and collected over a period of 100 years from the 1830s to the 1930s, the works vary in style, quality of workmanship, colour, composition and subject matter.

From as early as 1879, the V&A acquired its Kalighat collection gradually through direct purchase or by gift. The earliest purchases were two paintings that were originally part of the India Museum collection. Both paintings depicted secular themes: a seated Bengali babu (a foppish male figure, with a mix of Bengali and Western style), and an illustration of Jackal Raja’s court.

Kalighat painting gained international attention in 1895, when Maxwell Sommerville donated fifty-seven paintings to the University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology, USA. Following this, On 8th August 1917, John Lockwood Kipling’s personal collection of 233 works were donated to the Victoria & Albert (V&A) Museum, London, UK, by his son Rudyard Kipling. Kipling was a sculptor and teacher, and Curator of the Lahore Museum in the late 1870s, thus became the owner of largest collections of Kalighat paintings in the world.

Another significant source was that of W.G. Archer, Keeper of the Indian Section at the V&A in the 1950s, who oversaw the acquisition of 90 Kalighat paintings.

Interestingly our own Indian Kalighat Paintings can be found as exhibits in many foreign notable institutions like

* Bodleian Library, Oxford, Library has 110 paintings.

* The India Office Library collection, now part of the British Library, London has 17 paintings.

* The National Museum of Wales in Cardiff has 25 paintings.

* Naprstek Museum of Prague holds a collection of 26 works.

* The Pushkin Museum of Graphic Arts, Moscow has 62 works.

* The University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology, Philadelphia holds 57.

* Unfortunately, the Kalighat paintings do not appear on the walls of Indian Houses.

In India, the most prominent Kalighat collections can be found at museums across Kolkata, including the Victoria Memorial Hall; the Indian Museum; the Gurusaday Museum; the Birla Academy of Art and Culture, the Asutosh Museum; and Visva-Bharati University Kala Bhaban, Shantiniketan.

Kolkata, as unofficially accepted cultural capital of India, has pioneered several movements and trends in literature, cinema and theater, performing arts, etc. over the past centuries. Many of those are worldwide acclaimed but however the Kalighat Paintings remained unknown to Indian community. Kalighat painting, a school of art founded in the city during the 19th century, is among those rich legacies the country continues to bask in today.

The alternate discipline of Kalighat painting, known as the “Occidental school,” included pieces that depicted ordinary people engaging in everyday life or captured the changes taking place in Kolkata at the time. A N Sarkar & C Mackay

remarked that “The Kalighat school of painting is perhaps the first school of painting in India that is truly modern as well as popular. With their bold simplifications, strong lines, vibrant colours and visual rhythm, these paintings have a surprising affinity to modern art”.

Acknowledgements:

Acknowledgements:

http://chitrolekha.com/kalighat-paintings-review/

https://mapacademy.io/article/kalighat-painting/

https://www.google.co.in/search?q=kalighat+painting&tbm=isch&tbo=u&source=univ&sa=X&sqi=2&ved=0ahUKEwjVkpzKkeLUAhVIw7wKHbHFAFQQsAQILA&biw=1188&bih=532&dpr=1.1

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lYPB6KcBgY8

https://www.vam.ac.uk/articles/kalighat-painting?srsltid=AfmBOorMyW9AZ703-9qUyGrNlxa_RAJfF8H3GOfJHkPYz4RiJ08xXEf5#slideshow=4207388&slide=0

1. Ajit Ghose, “Old Bengal Paintings”, Rupam, Calcutta 1926

2. Mukul Dey, “Drawings and Paintings of Kalighat”, Advance, Calcutta, 1932. (Courtesy: http://www.chitralekha.org/articles/mukul-dey/drawings-and-paintings-kalighat)

*******

৭০ ৮০ দশকেও কলকাতার কিছু জায়গায় রাস্তায় ফুটপাথে হকারদের বিক্রি করতে দেখেছি। তারপর জানি না কবে এটি বিলুপ্ত হয়ে গেলো।

আজ এখন এই লেখাটা পড়ে আবার মনে পড়ে গেলো। সম্ভবত আজকের মার্কেট কম্পিটিশনে এই প্রাচীন শিল্পটি আর ফিরে আসতে পারবে না।

খুব ভালো সহজ ভাষায় লেখা একটি প্রবন্ধ পড়ে ভালো লাগলো।

I am not a Bengali, and not so aware of such specific traditional arts. Oil painting on cotton is common historically but what I understand from this article is that these were story tellers based on certain topics. It’s unfortunate if such traditional practices are now abandoned and there is no social patronage.

Thanks author for sharing a forgotten traditional art practice, though it’s painful to accept.

Bengal was always in limelight for creative arts. Bengal was also known for patronage of its traditional art practices. It’s surprising that such a household item becomes redundant. Thanks for those European museums that they are preserving these.

সুন্দর উপস্থাপনা। সহজ করে লেখা, পড়তে ভালো লাগে, আর অনেক কিছুই জানা হলো।

দুর্ভাগ্য, আজকের প্রতিযোগিতায় একে ধরে রাখা গেলো না। তবে সরকার বা বাণিজ্য মহলের ঐকান্তিক ইচ্ছা থাকলে আমাদের জাতীয় মিউজিয়ামে কিছু কিছু প্রাচীন কারুকার্য হয়তো সংরক্ষন করা যেতো।

Somewhere I have read about it earlier.

These paintings had its classic and distinct identity till the mid of last century. Initially they were depiction of Hindu Gods and mythological characters. Sad that slowly it lost its market due to socio-economic reasons.

Thanks for the museums who are preserving some of these.

Thanks for the author for the nice article.

Very nice documentation of an important school of painting of Bengal. Well researched article. Keep on writing, please.

কালীঘাটের অনুকরণে মেদিনীপুর আর বীরভূম জেলাতেও একসময় অনেক পটুয়া ছিলেন। বিষয়বস্তুও মোটামুটি একইরকম, দেবদেবী বা সামাজিক। বাংলায় কিছু পটুয়া এখনও আছেন, কিন্ত ক্রেতার অভাবে আর বেশিদিন চলবে না।

কালীঘাটের পটচিত্র সম্পর্কে এত সুন্দর লেখা ….. পড়ে খুব ভালো লাগলো। এই পটচিত্রের উৎপত্তি ও ইতিহাস ….. জানতে পারলাম।

এরকম লেখা আরো পেতে চাই ।

কালীঘাট পেইন্টিং নিয়ে এতো সুন্দর লেখা আগে আমি পাই নি। প্রচুর তথ্য সংগ্রহ করে এই লেখা লেখক লিখেছেন, আর এরসাথে বেশ কিছু ছবিও এই লেখার সাথে দেওয়া হয়েছে। অপূর্ব লেখাটা। আমাদের বাংলার গ্রামের কিছু লোকজন প্রথম কালীঘাটে এসে এই অপূর্ব শিল্প কলার জন্ম দেন। তারপরে ধীরে ধীরে এর বৃস্তিতি এতটাই ছড়িয়ে পরে যে আমাদের দেশ ছেড়ে এই শিল্প কলা বিদেশের বিভিন্ন জায়গায় ছড়িয়ে পরে। এই শিল্প কলা এতটাই বিখ্যাত হয়ে যায় যে ইংল্যান্ডের musium এ এর জায়গা হয়ে যায়। লেখক কে আমার আন্তরিক শুভেচ্ছা রইলো এতো সুন্দর একটা লেখা আমাদের সামনে উপস্থিত করার জন্য। 👌🏽👏🏽❤

অসাধারণ তথ্য সমৃদ্ধ লেখা। অনন্য সুন্দর ছবিগুলি লেখাটিতে অন্য মাত্রা যোগ করেছে। লেখার শৈলী অত্যন্ত সাবলীল যা পড়ার আগ্রহ বাড়িয়ে তুলেছে। আরও এরকম লুপ্ত প্রায় শিল্পকে সামনে নিয়ে আসার অনুরোধ রইল! অনেক ধন্যবাদ।

আমাদের পারিবারিক সংগ্রহে কয়েকটি পটচিত্র আছে, ভালোভাবেই সংরক্ষন করা হয়েছে।

এই প্রবন্ধটি পড়তে পড়তে মনে হলো যে সময়ের সাথে, মানুষের পছন্দ পছন্দের সাথে আর নতুন নতুন প্রযুক্তির ব্যবহারে শিল্পের পরিবর্তন অবশ্যম্ভাবী। আমরা কেউ আটকাতে পারবো না। কিন্তু শিল্পটি অবলুপ্ত হয়ে যাবে এও মানতে পারি না।

লেখককে অসংখ্য ধন্যবাদ এই প্রবন্ধটি শেয়ার করার জন্য।

কত পুরানো হারিয়ে যেতে বসা চিত্র শিল্পের তথ্য ভিত্তিক আপনার উপস্থাপনার জন্য আন্তরিক ধন্যবাদ জানাই।

এই শিল্পের সাথে সেই ছোটবেলার পরিচয়। বছরে দুই তিনবার গ্রামে পটুয়ারা আসতেন। লম্বা চিত্র পটে ছবি দেখিয়ে বিশেষ একটা মনকাড়া সুরে বিশেষত নীতিবোধের প্রচার হতো। সেই বাণী সুর

ছোট মনে বেশ প্রভাব ফেলতো। তারপরে কোথায় হারিয়ে গেলো। এতো বছর পর আপনার লেখা পড়ে কয়েকজন শিল্পীর নাম জানলাম তাঁরা নমস্য।

প্রথম কলকাতায় আশির দশকে কালীঘাট গেছি অনেকবার তখনও পটচিত্র বিক্রি হতো। পরে আর তেমন ভাবে দেখিনি।

অনেক ধন্যবাদ আপনাকে ফিরে দেখালেন একটুকরো সুখ স্মৃতি।

আপনার

লেখাটা পড়ে যেমন ভালো লাগছে, তেমনি আমাদের এত প্রাচীন নিজেদের কারুকার্য শিল্প এভাবে হারিয়ে যাচ্ছে এই সত্য কথাটিও মানতে পারি না।

কিছু পটুয়া এখনও আছেন, নানান ছোটখাটো মেলায় পসরা সাজিয়ে আনেন, কিন্তু কতটুকু উপার্জন হয় জানিনা।

খুবই দুঃখের পরিণতি।

Fascinating write up about our own school of painting. Please continue writing such informative post.

Very well written. The paintings are beautiful & thoughtfully chosen. They have their own “gharana”, if I am permitted to say.

I read the article at one sitting. Though I am not an art critic, the description of Asim Deb is so simple and interesting that I never felt a novice about art of paintings.

The article is very much informative and pleasure to go through with curiosity enriching knowledge.

Nice collection of Kalighat paintings in your article. Artists are rarely appreciated now a days as you written for availability of cheap commercial painting.

Once we went IIT, Kharagpur to meet one of our family friends . We stayed there 2 days. One day we went to nearby Pingla village to see their painting work. Almost all the families in village were engaged in painting work . They were also using natural colour to paint on scroll papers. We came to know that they also paint on the sarees. My wife contacted them from Kolkata for painting few sarees. They came to our house in Kolkata & collected the sarees. After 10days or so the potuas came with sarees with beautifully painted. It was very nice .

The famous Kalighat painting – known as ‘Potchitra’ in Bengal and the artists who used to paint those Potchitra – known as ‘Potua’s, have become a matter of past since 1930. The heritage of this genre of painting dates back 1830 and continued to flourish till 1930. This write up on “Kalighat painting” is a precise and mini journal on the glorious achievements of local artisans of Kalighat, Kolkata, and their prominent presence in the famous Kalighat Temple and it’s adjoining areas. It is really remarkable that the artistic excellence of the Potua’s is now preserved as souvenir almost worldwide in various museums.

Thanks to author Asim Deb for Another piece of informative write up.

পটু হাতে পটচিত্রের পটভূমিকা পরিবেশন।

বাংলার এই প্রাচীন শিল্পটি আজ বিলুপ্তির পথে। থিমের চাপে, পটুয়ারা বেছে নিচ্ছেন অন্য জীবিকা। লোপ পাচ্ছে বাংলার লোকসংস্কৃতির পটের গান বা পটুয়া গীতি।

কয়েকটি গান বেশ ভালো:

পঞ্চ কল্যাণী গীতি:

“নম মহেশ্বর দিগম্বর ঈশান শঙ্কর।

শিবা শম্ভু শূলপাণি হরা দিগম্বর।।”

কৃষ্ণ প্রিয় গীতি:

“হরি বিনে বৃন্দাবনে আরা কি ব্রজে শোভা পা।

জলে কৃষ্ণ স্থলে কৃষ্ণ কৃষ্ণ মহিমন্ডলে।”

I am neither a critic nor a connoisseur of painting. Yet, this lucid piece of Asim on the bold line and creation of painting in a single stroke of brush is amazing. Some Jamini Roy painting in the Kaligghat pot style, that I have seen, also supports Asim’s contention. Really, that level of aesthetic creation without lifting the brush, even once, is unusual and very original.

Asim also explains how the various pigments are developed by the unknown yet marvelous plebian artists.

I would like to add one thing.

May parents from erstwhile East Pakistan, now Bangladesh, told me about the similar tradition of Potua and Patchitra in that region.

In autumn , when the work in agriculture fields completed, those people with a stack of such paintings used to roam villages singing and narrating tales while displaying those paintings.

A few lines from my memory (in Bengali ):

I am not a critic of paintings as such. Yet, Asim’s narrative how Kalighat scroll paintings had been created by unknown plebian painters using a single brush-stroke. Nay, not lifting the brush once. Therein lies the mystery of their bold lines.

Yes, the few Jamini Roy paintings that I have perused– known for his adoption of Kalighat painting style in his mature days— also supports this narrative.

Again, Asim goes on unfolding the mystery of the pigments of native bright colours used in Kalighat scrolls. I scratch my ear. Why I did not think of these aspects ever?

I would like to add a little to Asim’s narrative of sub altern history.

Both my parents are from erst while East Bengal, now Bangladesh. They told me similar tradition of scroll painting there. They called it Patua or Patchitra tradition.

In autumn, when folks got free from work in agricultural fields, those patuas used to roam from village to village, displaying the scrolls with songs and story telling.

A few lines from my memory (in Bengali):

” পিডুর পিডুর ম্যাঘ পড়ে, কই যাও রে ভাই?

রাজার পুতে হুকুম দিছে বাঘ মারিতে যাই।

এক বাঘ মাইরা আইলাম কইট্যা দীঘির পাড়ো,

আরেক বাঘ মাইরতে গেলাম জঙ্গলে পলাইল”।।

It is drizzling bro.

where do you go?

It is the royal order,

We are to hunt now tiger.

have killed just one

and left it beside the pond.

But I missed another

that fled to the jungle and beyond.

না জানা, হারিয়ে যাওয়া, এই সব বিষয় আমাদের সামনে তুলে ধরা তোমার বৈশিষ্ঠ আর সেটা এবারও তুমি খুব ভালভাবে সম্পন্ন করলে। পটচিএ একসময় ভালোই জানতাম, কারণ পুজো পার্বণ এবং অনেক অনুষ্ঠানে তাদের দেখা পেতাম। তারপরে তো কোথায় হারিয়ে গেল, ভুলেই গেলাম। কালীঘাটের পটচিত্র সম্পর্কে তোমার সুন্দর উপস্থাপনা খুব ভালো লাগলো। এই পটচিত্রের উৎপত্তি ও ইতিহাস জানতে পারলাম। প্রাসঙ্গিক পটচিত্রের ছবির সংগ্রহ খুব উপভোগ করলাম। ভুলে যাওয়া পটচিত্রের আবার আস্বাদ পেলাম। এভাবেই তোমার অনুসন্ধান চলুক আর আমরাও সমৃদ্ধ হই।

ছোটবেলার মাটির সরাই এ লক্ষী পট আর কখনও কখনও কাগজের উপর পৌরাণিক কাহিনীর পট চিত্র,আমাদের জ্ঞান এই অবধি সীমাবদ্ধ ছিল ।

লেখক অসীম কে অশেষ ধন্যবাদ। আজ আমরা অনেক কিছুই জানতে পারলাম।

খুবই তথ্য সমৃদ্ধ লেখা।অনেক অজানা ইতিহাস জেনে ভালো লাগছে। এই চিত্রকলা দেখা যায় পূজা মন্ডপের সাজসজ্জায়, বিভিন্ন মেলা প্রাঙ্গনে। এর গ্রহণযোগ্যতা যথেষ্ট রয়েছে বলে মনে হয়।

লেখককে সাধুবাদ জানাই।

Fascinating read.

I got to know many things, one among them is the ‘Potochitro’ word. I never knew why it was called so. The amazing art of ‘Patua’ tribe was indeed revolutionary. It’s a pity that this history has never been taught or discussed in academics.

Thanks to the writer for bringing such interesting part of history into light.